Hi,

Hepatitis --meaning inflammation of the liver-- most commonly comes about because of a virus. These

viruses tend to target the cells in the liver, and when they get in and infect

these cells, they tend to cause them to present these weird and abnormal

proteins via their MHC class 1 molecule. And at the same time, you’ve also got

these immune cells infiltrating the liver and trying to figure out what’s going

on. And so the CD8-positive T-cells recognize these abnormal proteins as a sign

that the cells are pretty much toast. The hepatocytes then go through cytotoxic

killing by the T-cells and apoptosis. Hepatocytes undergoing apoptosis are

sometimes referred to as Councilman Bodies, shown on histology here.

This typically takes place in the portal tracts and the lobules of the liver. This cytotoxic killing of the hepatocytes is the main mechanism behind inflammation of the liver and --eventually-- liver damage in viral hepatitis. As someone’s hepatitis progresses, we’ll see a couple of classic symptoms related to your immune system mounting an attack: fever, malaise, and nausea. Additionally, though, patients might have hepatomegaly, where their liver is abnormally large from inflammation --which also might cause some pain. As more and more damage is done to the liver, the amount of transaminase in their blood will increase. This is because your liver has these transaminase enzymes so it can do its job of breaking down various amino acids. Typically the serum amino transaminase --or the amount [found] in your blood-- is pretty low. But when your hepatocytes start getting damaged, they start leaking these into the blood, so a common sign is a greater amount of both alanine aminotransferase --or ALT--and aspartate aminotransferase --or AST.

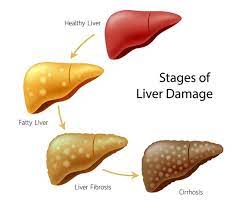

Another common finding is increased urobilinogen in the urine. Urobilinogen is produced when bilirubin is reduced in the gut by intestinal microbes. Normally, most of that's reabsorbed and transported back to the liver to be converted into bilirubin or bile again. But if these liver cells aren’t working right, that urobilinogen is redirected to the kidneys and excreted, so you end up with more urobilinogen in your urine. If symptoms continue, or the virus sticks around for more than 6 months, viral hepatitis goes from being "acute" to being "chronic" hepatitis. At this point, inflammation mostly happens in the portal tract. And if the inflammation and fibrosis keep happening, we consider that a pretty bad sign, since it might be progressing to post-necrotic cirrhosis. Now, there are five known "flavors" of hepatitis virus that have slightly different and unique properties.

Hepatitis A virus is transmitted through ingestion of

contaminated food or water, in other words, the fecal-oral route, and is known

to be acquired by travelers. Hepatitis A virus --or HAV, for short--is almost

always acute. And there is essentially no chronic HAV. If we’re talking about serological markers, an HAV-IgM antibody indicates an active infection; whereas

an HAV-IgG antibody is a protective antibody that tells us that there’s been

recovery from HAV or vaccination in the past. Hepatitis E virus is

actually pretty similar to HAV, with the same route of transmission

--oral-fecal. And is most commonly acquired through undercooked seafood or

contaminated water. It also doesn’t have much of a chronic state. And HEV-IgM

antibodies tell us that there’s an active infection and the HEV-IgG antibody is

protective and signals recovery --just like HAV. Two big differences to note,

though, between these two guys is that 1: only HAV has the option for

immunization; and 2: HEV infection for pregnant women can be very

serious, and can lead to acute liver failure, also sometimes called fulminant

hepatitis.

All right. Next on the docket is the Hepatitis

C virus. Now, this guy is transmitted via the blood. So it could be from

childbirth, intravenous drug abuse, or unprotected sex. HCV usually does move

on to chronic hepatitis. And there are a couple of tests that we use to help

diagnose HCV. One way is by enzyme immunoassay. In this case, we’d screen for

the HCV-IgG antibody. If present, it doesn’t necessarily confirm acute, chronic,

or even resolved infection, because it isn’t regarded as a protective antibody-like it is in HAV and HEV. To get more specific confirmation, you might use a recombinant immune-blot assay, which helps confirm HCV. It’s more specific but

less sensitive than immunoassay. Clinically, recombinant immune-blot assay

doesn’t provide much usefulness and actually needs an additional, supplemental

test if it's positive. That being said, the gold standard for HCV diagnosis is

an HCV RNA test. Using PCR --or polymerase chain reaction-- this method

can detect the virus very early on--as early as one to two weeks after

infection. Basically, it detects the levels of viral RNA in the blood, which

tells us the levels of virus circulating. If RNA levels begin to decrease, we

know that the patient’s recovering; if RNA remains the same, the patient

probably has chronic HCV.

On to hepatitis B. HBV is just like HCV in that it’s contracted via the blood. So [it's through] the same routes --like childbirth, unprotected sex, and others. HBV, however, only moves on to chronic hepatitis in twenty percent of cases overall. But it also depends on the age that which someone gets infected. For example, children less than six years old are most likely to get chronic infections --about fifty percent. And that percentage increases the younger they are. Also, chronic HBV is known to be linked to liver cancer. And all these things make HBV and the serology of HBV a super-important concept to understand. And kind of like hepatitis C, we can use a variety of testing methods --like PCR-- to look for certain markers, especially the HBV antigens. And the presence --or absence-- of each of these, at different time points, can tell us different things. All right. So the key marker for HBV infection is the HBV surface antigen. And this is going to be like the super-villain in this story. And this evil-doer lives on the surface of the virus --here-- and we can call it HBsAg --meaning: Hepatitis B surface antigen. Another marker, though, is a core antigen--meaning that these antigens come from the core of the virus-- HBsAg. Think of these as the dispensable henchmen that work inside the villain’s evil factory. Finally, there’s this other antigen--called the e-antigen-- which is secreted by infected cells; and so, it's this marker of active infection. These are like the by-products of the factory. And along with viral DNA, they tell us that it’s replicating and infecting. All right. So at the onset of infection, during the acute phase, our surface antigen super-villain will definitely be present and will come up positive. And its factory will be pumpin’ out both viral DNA and e-antigen. At this point, the immune system produces IgM antibodies against the core antigens--against the henchmen--so think of these like your basic police force that works against the core henchmen.

These antibodies hack away at the core antigens and they really try their hardest. But in order to actually defeat this villain, this virus, you need to go for the super-villain, The surface antigen. So, we need a superhero to go after it. So, in this story, the IgG antibody for the surface antigen is our superhero. At this point, the host enters this spooky phase called the window, where neither the super-villain nor the superhero can be detected because they’re both so low, and this can last from several weeks to months, it’s like this war’s being waged but we don’t know who’s coming out on top. The only thing you can detect during this stage is the IgM core antibodies, the police force. At this point, two things can happen, if the superhero comes out, the IgG antibodies to the surface antigen, then we’re golden, and this means the day is saved and we win. The other possibility is that the super-villain wins, and surface antigens are still, again, detected, there may also be a presence of HBV DNA and e-Antigen because it’s now replicating and the factory is up and running again.

The main point though is that there will not be the IgG for surface antigens, our superhero. Regardless of whom wins, the IgM antibodies, the police force, will be promoted to IgG by about 6 months' time, but this does not mean that the host is protected. So it’s important to note that we need this surface IgG superhero to win, but we can have core IgG and still lose. If the battle’s lost, the host transitions into chronic viral hepatitis, defined by it continuing after 6 months. When chronic, the host could present as, sort of healthy, and will likely have the presence of surface antigen, core antibody, and no DNA or e-Antigen, basically saying that the super-villains there, it’s just not replicating, and at this point the host is contagious, but there’s lower risk. The other option is that they’re infective, meaning the whole villain force is active along with an overwhelmed police force. This state increases the risk for post-necrotic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma or HCC. One way to get around this whole fiasco is by immunization, which skips these steps and gets you right to the IgG superhero antibody for surface antigen.

Alright, last but not least, well

maybe it's the least, I dunno. Anyways, the Hepatitis D virus is unique in that it

needs HBV, meaning that it can only infect the host if that host also has HBV.

If it infects at the same time, it’s called co-infection, if it infects

sometime later, it’s called super-infection, which is considered to be more

severe than co-infection. If either the IgM or IgG antibody is present, that

indicates an active infection, so in this case, the IgG is not a protective

antibody.

This is a very brief overview of

viral hepatitis. Hope you guys get it.

.jpg)